by Petra Caruana Dingli

‘Gwardjani tar-rahal’ by Stephen C. Spiteri

‘Gwardjani tar-rahal’ by Stephen C. Spiteri

We can all think of imaginary places which we wish we could visit. Perhaps Tolkien’s Middle Earth, or the world of the Game of Thrones. These are fictional, magical landscapes which resonate in the imagination. Old European tales include forests, mountains and castles, picturesque towns and small, rural villages, just like these. The places are imaginary, but they are based on the real, old landscapes of Europe.

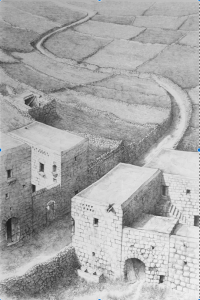

The Maltese Hal Niesi is such a place, a fictional but real village with its old houses, alleys, and winding country roads. It is the subject of a collection of pen drawings which have just been exhibited at the National Library in Valletta by artist and historian Stephen C. Spiteri.

These drawings skillfully present slightly elevated aerial views and quiet corners of Hal Niesi, the forgotten hamlet – a play on the word ‘niesi’, my people, and forgetfulness, from ‘nesa’. They merge mental images and memories of places which were once just like this. Instead of the village of forgetting, this could also be called the village of remembering.

If we had a long tradition of Maltese fairy or folk tales, this is the kind of place in which they could be set. The drawings are accompanied by a story by John Spiteri Gingell, the artist’s brother. He recounts the experience of an old man who once found himself in Hal Niesi, but then could never find it again. Years later he came upon a drawing of it at an art exhibition and realized that Hal Niesi did exist after all, and that others had also been there, like him.

There is of course much more than an opportunity for a fairy tale in these images. In truth, we no longer really have any remote villages like this. The drawings explicitly evoke a set of emotions and thoughts. Those of us old enough to remember tranquil hamlets in Malta and Gozo will not only recognize the stones but also the atmosphere of the place. We have been to Hal Niesi.

This is not just nostalgia or sentiment. An artistic contemplation of ruins and vanishing places also has social and political echoes. How do we feel about this lost world? Spiteri explains that the drawings are a “personal nostalgic sentiment inspired by the spirit of Malta’s disappearing rural landscapes, abandoned rustic buildings and forgotten refuge spaces.”

A key word here is ‘disappearing’. In the foreword of the catalogue, Philip Farrugia Randon laments that we “have severed our umbilical cord” which connected us with these rural scenes, the reality of past generations. At the exhibition launch, historian Henry Frendo addressed the audience and spoke of the ravages of excessive construction that Malta is facing.

Spiteri’s pen traces the sculptural and aesthetic qualities of the architecture and landscape. The lines of stones and rubble walls are not symmetrical but flow organically into one another. The images tempt you to step into Hal Niesi and imagine what happened in those intriguing spaces, and the people and events which passed through.

An artistic tradition of a fascination with ruins is especially associated with Romantic poets and painters at the turn of the nineteenth century. In their decline, ruins resemble unfinished buildings which attract the spirit and the imagination, as well as the eye. Ruins capture our attention because they do not only speak about the past, but of the future. They provoke reflections on loss and renewal. Old houses are more than an accumulation of stones. They are a repository of memories. We are seduced by the mystery of old places, their dark corners, their faded and distant stories.

Today Malta’s lost villages are not ruins, or forgotten. They have vanished. They have grown and changed, and are gradually being demolished to make way for new buildings. Every day we hear of more destruction of old, vernacular, traditional village houses.

Here and there, you can still find isolated buildings and roads which resemble the houses and roads of Hal Niesi, but they no longer form a wide landscape. Just a few minutes away there is probably a traffic-congested street or shops and offices.

There are no human figures or signs of daily life in the silent landscapes of these drawings, creating a slightly sinister, desolate feeling. Where is everyone? Has something bad happened here? Has everyone fled or died? A ghostly stillness has settled on these old country lanes and farmhouses. The people have gone.

Everything finishes and fades away in time. The drawings are nostalgic but not pessimistic. Such images can make us fear the future by showing us what has already been lost. But they are also a memorial to the rural past and a celebration of it.

24 September 2017

Comments are closed.